In Conversation with Alfredo Häberli

Rethinking Form, Culture, and Contemporary Design

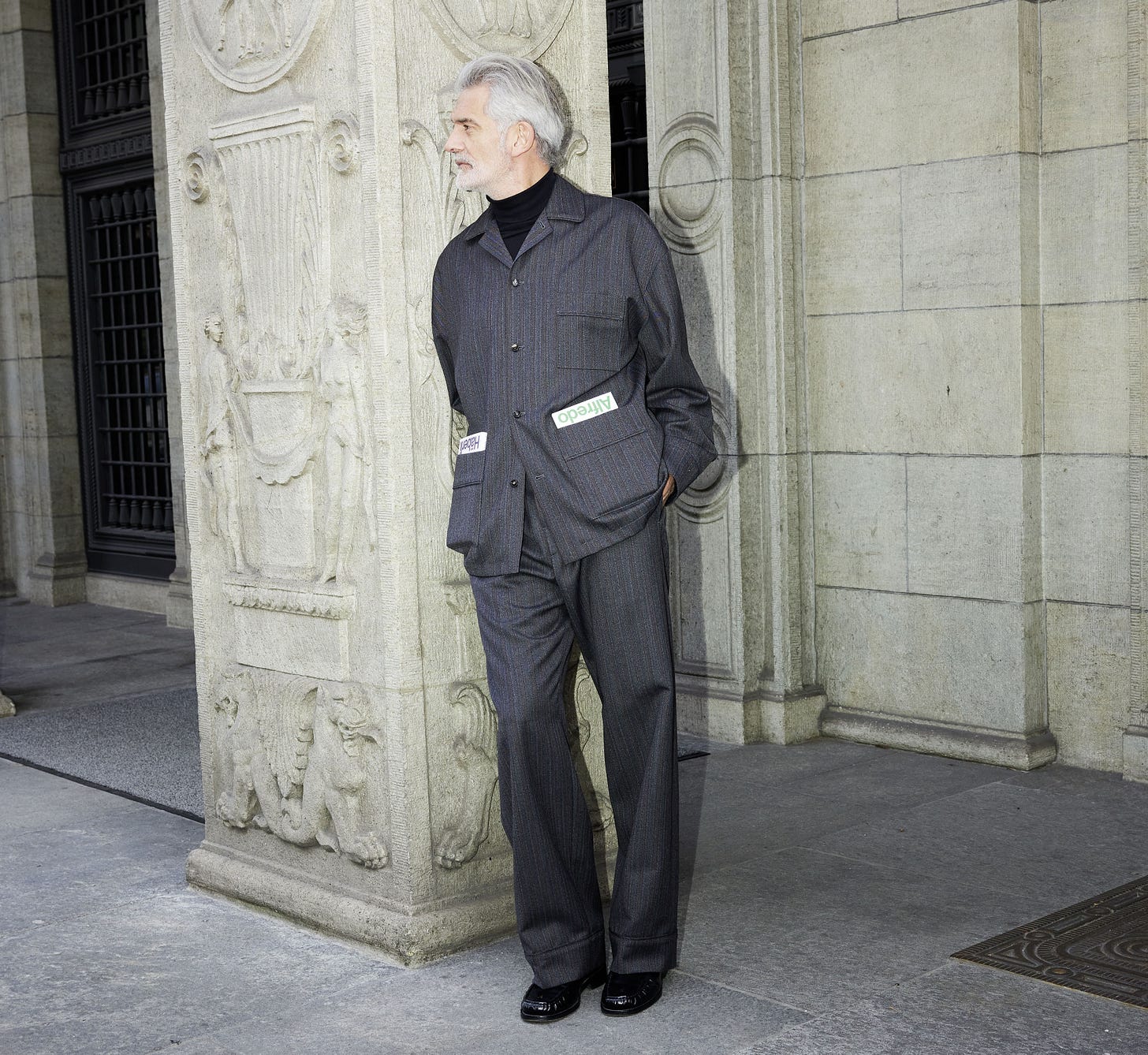

Alfredo Häberli is one of Switzerland’s most influential designers. A voice whose work moves effortlessly between tradition and forward-thinking innovation. Born in Buenos Aires and raised in Zurich, he has spent decades shaping contemporary design through a blend of emotional clarity, precision, and a deep curiosity for everyday life.

His portfolio spans collaborations with leading global brands: reimagining forms for Porsche, creating timeless furniture with Vitra, and developing iconic glassware and objects for the Finnish design house Iittala. Across disciplines and scales, Häberli’s work carries a distinct sensitivity, an ability to distill memories, materials, and cultural contrasts into designs that feel both familiar and entirely new.

This conversation explores the inner landscape behind his practice: his way of seeing, interpreting, and reshaping the world, and what continues to drive his creative evolution after more than three decades in the field.

In what ways does your childhood in Buenos Aires still influence your work and your perspective on design today?

I still draw on the images, smells, and colors of my childhood. I had a very beautiful time in Argentina. It remains a source, sometimes as direct inspiration, often simply as a feeling that has stayed with me to this day.

How did moving to Switzerland reshape your perception of culture and aesthetics?

The contrast was enormous. Buenos Aires is very European in spirit, yet Switzerland, its small scale, its precision, its care, was something completely different. Studying here shaped me deeply: the design, architecture, and art history; the workshops; the materials; the infrastructure. As a non-Swiss, all of this felt like a luxury, and I made full use of it.

Were there particular figures who have especially influenced you?

Yes. Missing Argentina led me to Milan, where I truly discovered the profession of the designer. Before that, architecture was my path. In Milan I encountered Achille Castiglioni and Enzo Mari. They became my favorite designers and my inner guardrails, especially in those uncertain early years. When all you have is a feeling and a vision, such figures help you stay on course.

“I never had a Plan B. There was only this direction.”

Was it clear to you from the beginning that you would stay in design, or was there some uncertainty?

Not at the beginning. But once I saw the profession of the designer and the faces behind it, it became clear: that’s where I want to go. I wanted to be in Milan, at the furniture fair, in those showrooms. I never had a Plan B. There was only this direction, and every step I took eventually led there.

How would you describe the core of your work or identity today?

It’s a mix of Swiss precision and poetry. I always look for an added value, a small invention, a discovery, in whatever field I’m working in. On one side there is the linear, investigative part; on the other, the emotional, unnameable quality. I don’t have a formal signature or a recipe. I think in approaches, and I always work together with industry. Developing an idea within their limitations and possibilities is at the core of my practice.

You often mention being inspired by everyday life. What exactly do you look for in the everyday?

When I have a topic in mind, I see possible solutions everywhere. The objects around me stay the same, but the questions change, and with them their meaning. I need to see in order to think, and intuition guides me. At the beginning I deliberately block out what supposedly isn’t possible. I allow everything before narrowing down, that’s a central part of creativity for me.

You describe your studio as a space that feeds your soul. Are there objects or materials you continually return to?

I am especially fascinated by old materials: wood, glass, wire. They feel closer to me than something purely synthetic. Wood accompanies me from vessels to furniture to structures; it’s simple and strong at the same time.

How would you describe your creative process, and how do you navigate moments when uncertainty, risk, or blocks become part of it?

At the beginning, I open myself to everything, images, sketches, sentences, books, objects, without judging. This first phase is fragile, but beautiful. Only afterwards do I try to understand why exactly these images appear, look for connections, and condense them into a theme. That’s how the process begins, step by step, never entirely linear.

“My studio is my laboratory.”

Which routines or systems support you in consistently producing good work?

If I’m not traveling, I go to the studio every day. The studio is my laboratory. This regularity is essential. And when things aren’t flowing, the “Wunderkammer” helps, a corner of the studio filled with books, materials, and collected objects. It always brings a smile and eases the pressure.

How do you structure your projects, and how do you navigate their scope over time?

We grow temporarily depending on the project, but at our core we are two to four people. Projects take longer today, often several years. What matters is not losing focus: returning to the original idea, to “What is this really about?”, because both the project and oneself change over time.

“In the age of AI, we designers become more important.”

With AI evolving so quickly, what role does it play in your work?

AI cannot replace the time certain things need. A project like the golf clubs for Golfyr took ten years, because of invention, patents, testing, and industrialization. AI can speed up certain steps, perhaps the form, but not the actual journey: the search with engineers, the testing, the making.

For me, AI covers about 80 percent of taste and makes many things interchangeable. That is precisely why we designers become more important. The remaining 20 percent make the real difference.

AI pushes everything to move faster, to shorten processes, but quality takes time. And in the end, the essential question remains: What is my taste, my point of view, and do I hand that over?

How has your understanding of design changed since you started?

Today I have more knowledge and can carry more complex projects. My attitude has remained the same: not following trends, achieving a lot with minimal means, and creating things that last. What has changed is the scale, from simple objects to complex systems like shelving, cars, or golf clubs.

How do you make decisions when you need to balance intuition and analysis?

Both belong together. I know history, architecture, fashion, design well; this knowledge flows in naturally. In new fields I analyze first, but the first impulse is often intuitive. I rediscovered this through my children: they react immediately, without justification. I give that feeling space before I start reasoning.

How do you define taste, and how has it evolved for you over time?

Taste is a sum of personality, history, and experience, not a talent you simply have or don’t. It varies culturally and constantly changes. Sometimes you need the ugly to see beauty, or kitsch to recognize refinement. Working with many countries, I see there is no single taste, only many valid perspectives, and somewhere in between lies my own.

“Made by people, for people.”

What inspires you most in your work right now, and what continues to motivate you on a personal level?

People remain my greatest motivation. Made by people, for people, that is still the most important thing. In recent years I’ve had a motto: I only work with people I like. It’s not meant arrogantly, it’s honest. I spend time with my clients: we eat together, develop products, see each other also digitally. I want to experience understanding for my part of the work, and I want to offer that in return, with respect. That interests me deeply and is my greatest motivation.

What do you want to deepen or question in your work over the next years?

My studio and archive occupy me greatly. Thirty-five years of work are there, and I want to create a catalogue raisonné while my mind is still fresh. I’m sixty now, and this moment in life naturally invites reflection. I still have dreams: a children’s book, and a sailboat. I’ve always been fascinated by things moved simply by wind or muscle.

I want to do less, but better, together with industry. The challenge is convincing companies to take the time to think. More and more come to us because they don’t know how to move forward, and we help them develop realistic utopias: studies, research, ideas that can actually become real. That work is demanding, but deeply meaningful.

What guidance would you offer to someone at the beginning of their creative career?

Do what you truly love, and stay close to what pulls you. It takes courage to look less outward and more inward. Intuition is key: feel first, then think. And keep the inner child alive as long as possible.

Thank you to Alfredo Häberli for taking the time and inviting me into his studio.

The interview was originally held in German and translated into English.

An Ongoing Dialogue

Curated is an ongoing dialogue, a living system of ideas exploring design, technology, and culture through curiosity and conversation.

I’d love to hear from you, what’s been inspiring you lately, or what’s been shaping your sense of taste? Reply anytime or contact me directly via Instagram or LinkedIn.

Thanks for reading. If this resonates, forward it to someone who values taste, design, and technology as much as you do.